This article by Professor Jorge Sá was recently published on the blind-referee Review of Economics and Finance (UK).

Professor Jorge Sá is a senior research fellow at Peter F. Drucker and Masatoshi-Ito Graduate School of Management in Los Angeles, a Professor at ISG Business School, a Peter Drucker expert and a speaker on Peter Drucker.

(site: www.vasconcellosesa.com ; e-mail: associates@vasconcellosesa.com)

Read the full article below:

BREXIT AS AN OPPORTUNITY FOR BUSINESS

Authors: Jorge Sá; Natália Teixeira; Márcia Serra

Abstract:

This paper analyses Brexit as an opportunity at the micro and niche level, and not in a macro level. The

opportunities are twofold: substitution of UK exports to Europe; and shifting of a country (or company) export to the UK into other destinations. The methodology used to assess the opportunities created by Brexit evaluates the results from different perspectives based on the case study of Finland (analysis in absolute terms), the Netherlands (analysis in relative terms), and the case of the Irish company Green Isle Foods (both types of opportunities).

1. The impact of the Brexit agreement

Many articles analyse Brexit as a risk [(MacRae et al., 2021); (Graziano et al., 2021); (Tien et al., 2019); (Tien et al., 20192); (Hassan et al., 2020)] and at the macro level [(Portes, 2022); (Hobolt et al., 2022); (Pandzic, 2021); (Belke & Gros, 2017); (Johnson & Mitchell, 2017); (McGrattan & Waddle, 2020); (Topliceanu & Sorcaru, 2019)]. However, little analysis has been done at the micro or niche level.

According to Crowley et al. (2018), a renegotiation of a trade agreement creates uncertainty into the country’s economic environment. Several papers assess the impact of post-Brexit free movement restrictions in both the short and long term, making estimates that point to a negative impact on UK GDP per capita and marginal positive impacts on low-skilled wages [(Dhingra et al., 2016); (Portes & Forte, 2017); (Tetlow & Stojanovic, 2018)]. The exception is a study prepared by Economists for Free Trade which concludes that the UK economy will receive a significant boost from Brexit (Tetlow & Stojanovic, 2018).

Ebell & Warren (2016) assess the long-term implications of the EU exit deal, focusing on reductions in trade with EU countries and a slight rise in tariff barriers, lower foreign direct investment (FDI) and a reduction in the UK’s net tax contribution to the EU, with decrease on GDP rate compared with other economies, as well as in wages, but reduce long-run impact on unemployment.

The agreement between the UK and Europe brought good news at the trade level, no tariffs and quotas on products (Lozada et al, 2021); contingencies if, for example any party invokes the level playing field clause (Mariani & Sacerdoti, 2021); unresolved issues to be negotiated in the future, including everything concerning the financial services sector (Ameur & Louhichi, 2021); and bad news, as there are currently customs with rules and tests, VAT to be paid and various restrictions on the origin of products and cabotage movements, among others.

Therefore, businesses have been complaining of expensive paperwork, long queues and several logistic difficulties and even shortages have occurred at supermarkets. In short, the situation changed. And the trend is to worsen after the end of the transition period in June 30th 2021 (Marshall et al., 2021). However, rather than a risk, Brexit created creates a great opportunity. Indeed, two types of opportunities. Regardless if an entity is a country or a company.

2. The two types of opportunities created by Brexit

The Brexit deal has created opportunities to be reckoned with. The first type of opportunity is the substitution of UK exports to EU countries, with the key question being to define which products the UK exports a lot of, to which EU countries, and which coincide with products that our company (or country) also exports a lot of, but coincidentally very little to the above country(ies)? On the other hand, the value of each opportunity for a particular EU country and specific product is equal to its imports from the UK minus our own company or country. The second type of opportunity created by Brexit is actually turning a risk into an opportunity and involves moving our exports (company, country) to the UK to other destinations.

In this context, the question now is to analyse which EU countries, import a lot from the world, excluding the UK, the same products that our entity (country, company) is exporting considerably to the UK, but coincidentally these countries buy very little from us? The opportunity is worth, country by country, product by product, given by the difference between world imports (except from the UK) and from our own country or company. And regardless of the type of opportunity, the final output is always a list of the main importers, i.e. the main potential customers to be contacted.

3. The Methodology

The paper’s methodology produced significant results as it led to a small group of opportunities many times better than the whole set of alternatives. Both in the cases of countries and companies. In the example of Finland, next, the average value of the opportunities found is ten times the average value of the alternatives. And in the example of the Irish firm Green Isle Foods, to follow, the average value of the opportunities created is 37 times that of all other possibilities. These results were produced with a methodology with three basic characteristics: unit of analysis; selection criteria; and phases.

Regarding the unit of analysis, the Eurostat databases divide each country’s economy in 88 industries (defined with two digits), then (within the industries) in 615 segments (with four digits) and then these still in 5.400 niches (six digits code). Thus, e.g., the basic metals industry receives from the Eurostat the code 24; within it there are several segments, for instance basic iron and steel (code 2410), tubes (2420), wires (2434); and then the segment basic iron and steel (2410) is composed by the niches titanium (720291), iron and steel (730210), etc. Tubes (2420) can be used in stainless steel pipelines (730411) or for coating wells (730520), etc. Wires (2434) can be uncoated (721710) or galvanized (721720), and so on.

The present research will use niches as unit of analysis, of which there are 5400 in a country’s economy. Given that there are 26 EU countries (EU-28 less UK less our own country), that gives 140 400 (5400 x 26) alternatives to choose from. Both to substitute UK exports to the EU (first type of opportunity). And to replace our (country’s or company’s) exports to the UK (second type of opportunity). Since the aim is to focus, to select the very few best alternatives, that is crossings of (5400) niches by (26) countries, three selection criteria were used: value, importance and urgency. The first two in order to find the top priorities to substitute UK exports to the EU (first type of opportunity). And the third one, urgency, was added to create the best alternatives to our entity’s (be read as country, economic sector, such as agriculture, mining, industrial transformation, or company) present exports to the UK (second type of opportunity).

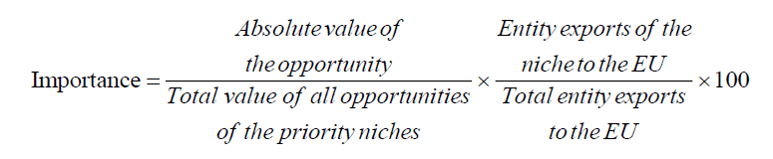

Value in the first type of opportunity is the difference between UK exports to a given EU country in a specific niche and the imports of that same EU country in that same niche from our entity (country or company). And value, in the case of the second type of opportunity, is the difference between imports by a specific EU country from the world excluding from the UK in a given niche and the imports of that same EU country in that same niche from our entity (country or company). The second selection criteria is importance. Regarding the first opportunity (substitution of UK exports) it is given by the formula:

The first ratio is an indicator of the relative weight (thus relevance) of a niche’s value. And the list of priority niches referred in the denominator have a cut point which simultaneously minimizes their number (to enable focus) and maximizes the sum of their value. The concrete cut point varies naturally from case to case. For instance, in the example of Finland to follow the cut point is 0,5% and in the case of Netherlands it is 1%. The other criteria were naturally that the opportunity value be positive (that is UK exports larger than that of our entity’s) and the latter greater than zero (to guarantee experience).

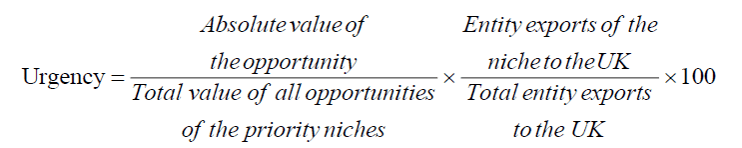

The second ratio of importance is an indicator of an entity’s competitiveness in a specific niche. Otherwise, that niche would not be an opportunity, but a distraction. Thus, the first ratio of the importance formula indicates relevance and the second competitiveness. Together they signal importance. In the case of the second type of opportunity (substitution of exports to the UK), the importance formula is similar with the single difference that in the second ratio, the EU is replaced by the world, to make it compatible with the value formula for the second opportunity: the goal now is to replace a given country world imports, not the UK exports to it. The third selection criteria, urgency, is used only in the second type of opportunity (shifting our entity exports to the UK into other destinations) and it is given by the formula below:

The first ratio is equal to that of the importance criteria and signals relative relevance. But now in the second ratio of the formula, exports to the EU are replaced by exports to the UK. The greater an entity’s exports to the UK the greater the need to find alternative destinations. Relative relevance (first ratio) and strength of need (second ratio) make for urgency. The final aspect of the methodology are the steps followed to create both types of opportunities as one moves sequentially from industries to segments to niches: the first two steps are different but the final one is equal.

The starting point in the first type of opportunity is UK exports to the EU and in the second it is our (country or company) exports to the UK. Then in the case of the first type of opportunity one looks for overlaps with our entity’s exports (signalling competitiveness for substituting UK exports); and in the case of the second opportunity, one focus on the level of our entity’s exports to the UK (an indicator of both need and competence). And the final step in both types of opportunities is the same: after finding the best niches, one divides each niche among the 26 EU countries and then one evaluates each crossing of niche by country in terms of the selection criteria of value, importance (for the first type of opportunity) and urgency too (for the second type of opportunity).

As said, the methodology was able to produce quite relevant results as the examples next will illustrate. Finland will be used as an example for the first type of opportunity. Netherlands for the second. And the Irish company Green Isle Foods for both [(Stack & Bliss, 2020); (Thissen et al., 2020)].

4. The Finnish economy as an example for the first type of opportunity

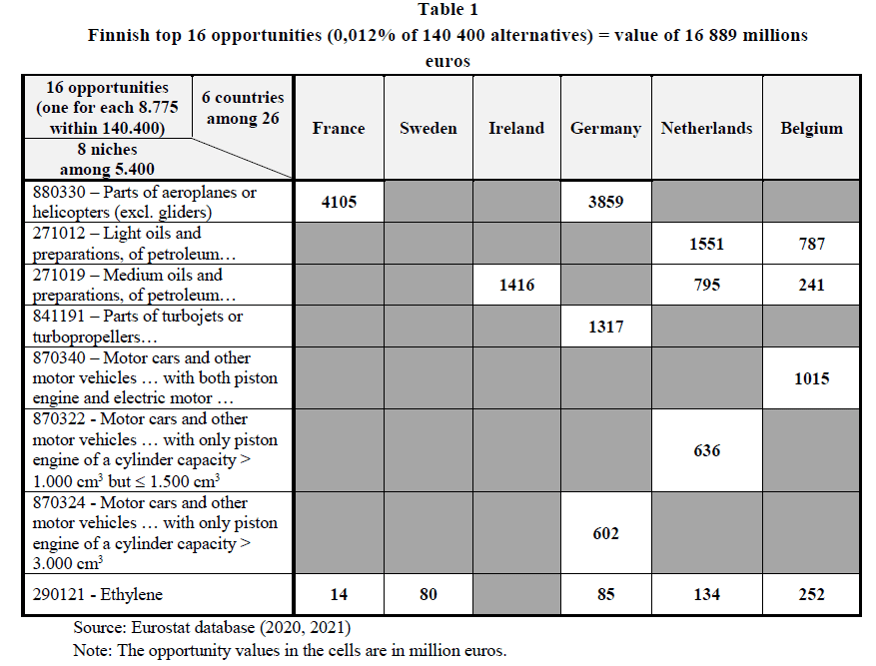

Table 1 shows the best sixteen opportunities for Finland to substitute UK exports to the EU. According to the methodology described above one listed the top ten opportunities in terms of value; also the top ten in terms of importance; and one deducted the common four to both tables.

The output is the sixteen priorities of Table 1, which indicate eight niches in six countries. Within the table is the value of each opportunity, namely, the niche 880330 (parts of aeroplanes or helicopters, excluding for gliders) create a value for substitution of UK exports of 4105 and 3859 million euros in France and Germany, respectively; niche 271012 (light oils and preparations) in Netherlands and Belgium value 1551 and 787 million euros respectively; next niche 271019 (medium oils and preparations) in Ireland is worth 1416 million euros; and so on.

Although these sixteen opportunities represent only 0,012% of the 140 400 alternatives (5400 niches in every economy multiplied by 26 EU countries – EU28 excluding UK and Finland), they are quite significant for two reasons.

First, their total value is 16 889 million euros (the sum of all opportunities in Table 1) representing 26% and 47% of all Finnish exports to the world and EU, respectively. Second, the results enable further focus, for instance in two small countries such as Netherlands and Belgium (right end columns of Table 1), whose eight opportunities value is 5411 million euros (the sum of all cell values under the Netherlands and Belgium columns), the equivalent of 15% of all Finnish exports to the EU. And these opportunities have ten times the average value of all 140 400 alternatives (26 EU countries x 5400 niches in each).

The potential clients, that is, the major importers in Netherlands and Belgium are companies such as (in niche 271012) Air Liquide Technische Gassen BV and Acol Smeermiddelen Center BVBA; (in niche 271019) Nijol Oliemaatschappij BV and Bondis BVBA; (in niche 870340) Van Hool NV and Vdl Bus Roeselare NV; and so on. Alternatively, instead of focusing on countries (Netherlands and Belgium), Finland may opt for concentrating on only a single niche (290121 – ethylene in the last line of Table 1) and in five countries (France, Sweden, Germany, Netherlands and Belgium) produces the total value for substituting UK exports of 565 million euros, equal to two percent of Finnish exports to the EU and with nearly twice the average value of all (140 400) alternatives. In such a case, the major importers and potential clients are now (in France) Prodix, (in Sweden) ExxonMobil Sverige AB, (in Germany) Helm AG, (in Netherlands) Caldic Chemie and (in Belgium) Chemogas NV.

5. Netherlands as an example of the second type of opportunity

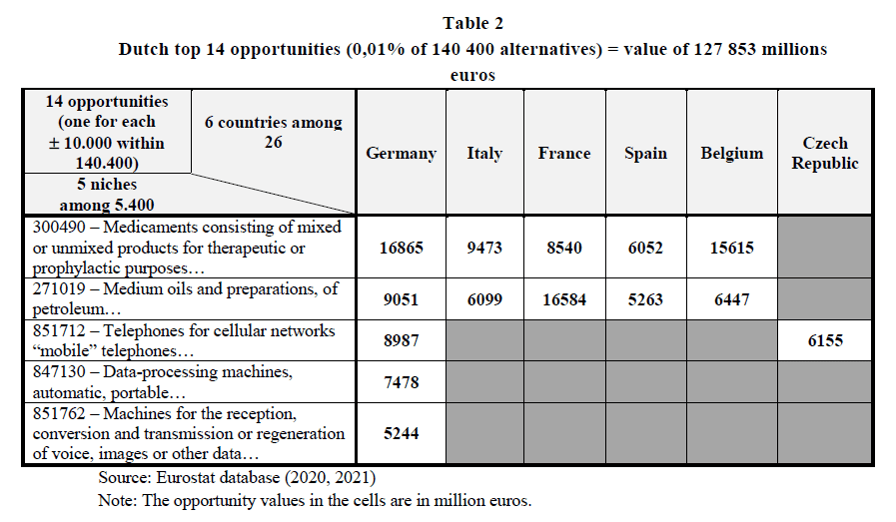

Table 2 presents the best fourteen opportunities for Netherlands to target on as an alternative to its present exports into the UK. And as described in the methodology section the selection criteria were three: value, importance and urgency. Thus, first one listed the top ten alternative targets in terms of value, the best ten in importance and the ten most urgent. And then one deducted the priorities common to the three top ten lists. The result is the fourteen opportunities indicated in Table 2, whose lines indicate the niches, the columns the countries and within the table, in each cell, are the opportunity values.

The priority niches are: 300490 (medicaments consisting of mixed or unmixed products for therapeutic or prophylactic purposes), 271019 (medium oils and preparations), 851712 (telephones for cellular networks), 847130 (data-processing machines, automatic, portable) and 851762 (machines for reception, conversion and transmission of voices, images); some in Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Belgium and Czech Republic as per Table 2. The total value of these 14 opportunities is 128 thousand million euros, again a quite relevant result for two reasons.

First, it amounts to 20% and 28% of Dutch exports to the world and the EU, respectively. And the priority niches have an average value 150 times the average value of all niches in the economy. Further focus in two small countries such as Belgium and the Czech Republic (right end columns in Table 2) and the three niches in those countries (300490, 271019 and 851712) have a total opportunity value of 28 217 million euros (15615+6447+6155) equal to 6% of all Dutch exports to the EU. The major importers in these countries and for these niches are Analis NV, Tecnolub SA, Chevron Phillips Chemicals International NV, TCCM s.r.o., among others.

6. The Irish company Green Isle Foods as an example of both types of opportunities

Green Isle Foods is an Irish firm with a turnover of 370 million euros and two brands: Dougal Catch (for fish and seafood) and Green Isle (vegetables, chips, potatoes, bread and pastries). It operates in nineteen niches, from Fresh or chilled filets of salmon (code 030441) to (waffles and wafers (190532). The others are the Frozen herrings(030351), Frozen blue whiting (030368), Prepared or preserved fish, whole or in pieces (160419), Frozen plaice (030332), Frozen fish of the families Bregmacerotidae and others (030369), Frozen hake (030366), Vegetables and mixtures, prepared or preserved, frozen (200490), Fruit, prepared or preserved (200899), Food preparations (210690), Vegetables, uncooked or cooked (071080), Frozen raspberries, blackberries, mulberries, and other berries (081120), Mixtures of vegetables, uncooked or cooked (071090), Spinach, uncooked or cooked (071030), Shelled or unshelled peas (071021), Potatoes, uncooked or cooked (071010), Potatoes, prepared or preserved (200410) or Bread, pastry, cakes, biscuits and other (190590).

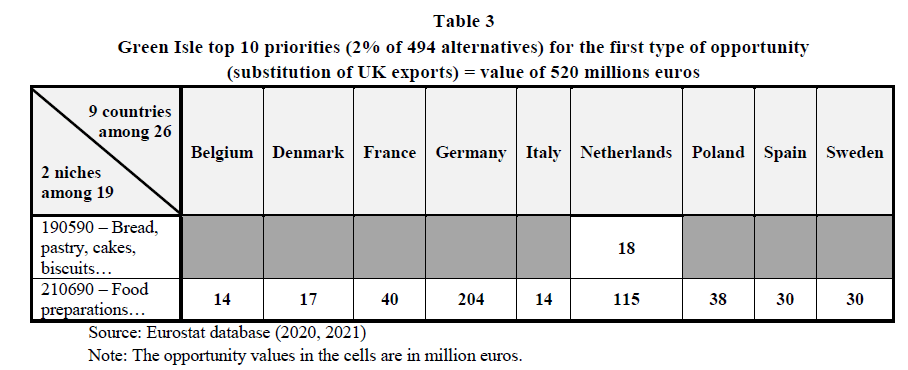

The 19 niches multiplied by the 26 EU countries create 494 alternatives for Green Isle, either to substitute UK exports to the EU or to shift its present exports to the UK into other European destinations. In the former case and using the same methodology used for the Finnish economy, one obtains the top ten most valuable opportunities and the top ten most important and – since all happen to coincide – the top priorities indicated in Table 3 are also ten.

There are two segments (190590 – bread, pastry, cakes, biscuits; and 210690 – food preparations) and nine countries from Belgium to Sweden. The ten priorities (2% of all 494 possibilities) have a total value of 520 million euros, 140% of Green Isle revenues. And with an average value 37 times the average value of all 494 alternatives. The focus in Netherlands (in both niches) only, in spite of being 0,4% of the total, have a value of 133 million euros, 36% of Green Isle’s turnover with an average value 48 times that of all 494 alternatives.

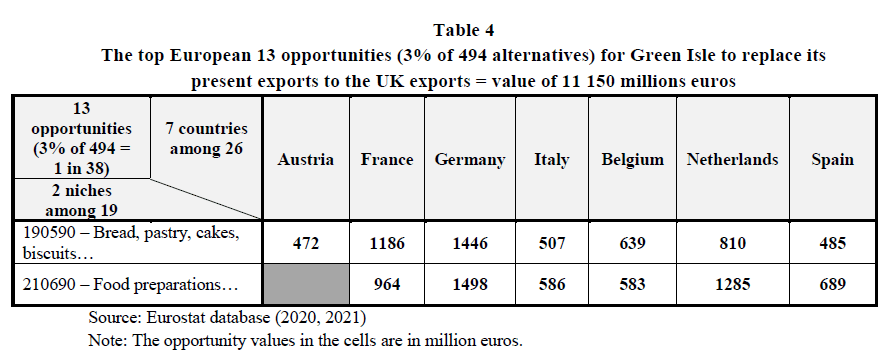

The main importers and consequently target clients for substitution of UK exports are Acatris Netherlands BV, Argentrade International BV, Henri BV and Hessing Zwaagdijk BV. However, if Green Isle’s objective was to find the best alternatives for its present exports to the UK and consequently transforming a risk into an opportunity, they are those indicated in Table 4. Their number is thirteen, the result of deducting those common to the lists of the top ten in value, top ten in importance and top ten in urgency too.

Two niches (190590 and 210690 pertaining to bread, pastry, cakes, biscuits and food preparations) in seven countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands and Spain), although only 3% of the 494 possibilities, have an opportunity value of 11 150 million euros, 30 times the company turnover and each opportunity values in average 15 times the average value of the 494 alternatives.

And again, further focus, e.g. on niche 190590 in three countries only (Belgium, Netherlands and Spain), solely create a value close to 2000 million euros (precisely 1934 million euros), five times the firm’s turnover and an average value eleven times that of all 494 alternatives. In such a case, the main potential clients are Zeelandia NV, Acatris Netherlands BV or Hotelsa Alimentación.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

This paper intends to analyse the Brexit process as an enabler of opportunities and not so much of threats, from a micro perspective. The methodology used in this paper to find the two types of opportunities created by Brexit (substitution of UK exports and exports to the UK), should be foremost evaluated by its results: in absolute terms, relative terms, and as they enable focus.

For the proposed analysis, different examples of countries and exported products were evaluated: Finland, the Netherlands and an Irish company, again strengthening the micro approach. In the example of Finland for the first type of opportunity, the methodology produced a list of sixteen priorities (0,012% of all 140400 alternatives) worth 47% of all Finnish exports to the EU; and with a further focus on Netherlands and Belgium, the outcome is a list of eight opportunities with an average value of ten times that of the alternatives, representing 15% of all Finnish exports to the EU.

The Netherlands exemplified the second opportunity and here the top 14 priorities (0,01% among all 140400 possibilities) represent 28% of Dutch exports to the EU; the priority niches have an average value of 150 times that of all niches in the economy; and three opportunities only are worth 6% of all Dutch exports to the EU.

Finally, the Irish company Green Isle Foods was used to exemplify both types of opportunities. The ten priorities (2% of all possibilities) for the first type (substitution of UK exports) are worth 1,4 times the company turnover and 37 times the average value of all alternatives.

Further focus enables to find two opportunities worth 36% of the firm’s turnover and 48 times the average value of the possibilities. And the list for the best thirteen (3% of all alternative) EU targets to replace the firm’s exports to the UK (second type of opportunity) value 30 times the company’s turnover, 15 times the average value of all possibilities and further narrow down on three opportunities only equal five times the firm’s turnover and 11 times the average value of all alternative targets.

The paper has some limitations that result from the limited application that was made. However, since the methodology is useful in terms of results, it would be interesting to use it – and regardless of improvements that others may wish to contribute to after this initial step – for further research in other contexts. Among them, two stand out. First, the opportunities created for European firms by the present USA-China trade war. Most specially in the USA.

Secondly, the analysis can be applied to the present economic context, with the constraints created by the Ukraine-Russian Federation conflict, assessing potential alternatives and ways to overcome the problems created.

Finally, the methodology can be applied to the reverse perspective of this article. Instead of how Brexit creates opportunities for Europe, to analyse how it creates opportunities for… UK firms. The UK has free trade agreements with several countries such as Canada, or Norway, among others. Thus, how can the problems of exporting and importing from the EU be transformed into opportunities for UK firms? After all, problems can be opportunities…

REFERENCES:

Ameur, H. B., & Louhichi, W. (2021). The Brexit impact on European market co-movements. Annals of Operations Research, 1-17.

Belke, A., & Gros, D. (2017). The economic impact of Brexit: Evidence from modelling free trade agreements. Atlantic Economic Journal, 45(3), 317-331.

Crowley, M., Exton, O., & Han, L. (2018, July). Renegotiation of trade agreements and firm exporting decisions: evidence from the impact of Brexit on UK exports. In Society of International Economic Law (SIEL), Sixth Biennial Global Conference.

Dhingra, S., Ottaviano, G. I., Sampson, T., & Reenen, J. V. (2016). The consequences of Brexit for UK trade and living standards.

Ebell, M., & Warren, J. (2016). The long-term economic impact of leaving the EU. National Institute Economic Review, 236, 121-138.

Eurostat (2021). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database, consulted in March

Eurostat (2020). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database, consulted in December

Hassan, T. A., Hollander, S., Van Lent, L., & Tahoun, A. (2020). The global impact of Brexit uncertainty, National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper No. w26609.

Johnson, P., & Mitchell, I. (2017). The Brexit vote, economics, and economic policy. Oxford review of economic policy, 33(suppl_1), S12-S21.

Lozada, H. R., Hunter Jr, R. J., & Shannon, J. H. As the American Song Goes:“Breaking Up Is Hard to Do”: A Comprehensive Review of Brexit, The Brexit “Deal,” And Europe, American International Journal of Business Management, 4 (1), 50-67.

Mariani, P., & Sacerdoti, G. (2021). Trade in Goods and Level Playing Field. Brexit Institute, Working Paper n. 7

Marshall, J., Jack, M. T., & Jones, N. (2021) The end of the Brexit transition period – Was the UK prepared? Institute for Government, IfG Insight, March 2021.

McGrattan, E. R., & Waddle, A. (2020). The impact of Brexit on foreign investment and production. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 12(1), 76-103.

Portes, J., & Forte, G. (2017). The economic impact of Brexit-induced reductions in migration. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33(suppl_1), S31-S44.

Stack, M. M., & Bliss, M. (2020). EU economic integration agreements, Brexit and trade. Review of World Economics, 156(3), 443-473.

Tetlow, G., & Stojanovic, A. (2018). Understanding the economic impact of Brexit. Institute for government, 2-76.

Thissen, M., van Oort, F., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., & Husby, T. (2020). The implications of Brexit for UK and EU regional competitiveness. Economic Geography, 96(5), 397-421.

Tien, N. H., Bien, B. X., Vu, N. T., & Hung, N. T. (20191). Brexit and risks for the world economy. International Journal of Research in Finance and Management, 2(2), 99-104.

Tien, N. H., Dung, H. T., Vu, N. T., & Duc, L. D. M. (20192). Brexit and risks for the EU economy. International Journal of Research in Finance and Management, 2(2), 92-98.

Topliceanu, Ș. C., & Sorcaru, S. L. (2019). The effects of Brexit on the European Unions economic power and implications on the British economy. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 15(6), 464-478.